Nekresi monastery

A saint doused a sacred flame and died for it. A pig saved a monastery from invaders. And beneath the forest floor, archaeologists discovered one of the oldest churches in the Christian world.

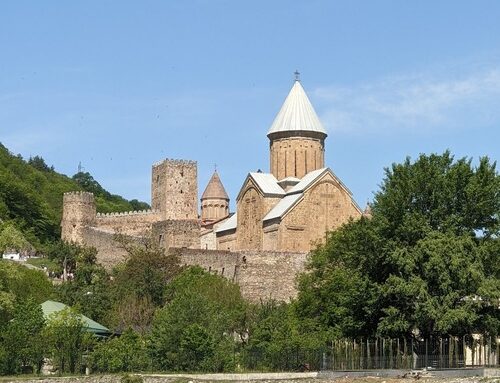

High above the Alazani Valley, where the Caucasus foothills are still thick with oak and beech forest, a cluster of ancient stone buildings crowns a hill called Nazvrevi Gora “the hill of former vineyards.” This is Nekresi Monastery, one of the most historically significant religious sites in Georgia, and one that played a unique role in the country’s struggle between Christianity and Zoroastrianism, between Georgian identity and Persian domination.

But Nekresi is more than a monastery. It sits atop the ruins of an ancient city that archaeologists are only now beginning to understand—a city that may have housed some of the earliest Christian churches ever built in the Caucasus, dating to within decades of Georgia’s official conversion. The discoveries here are rewriting the history of early Christianity in the region.

For visitors, Nekresi offers panoramic views of Kakheti’s wine country, a journey through 1,500 years of Georgian architecture, and encounters with traditions found nowhere else in the Christian world—including the only Georgian church where pigs are sacrificed in thanksgiving.

The Martyr Who Doused the Sacred Flame

No story captures Nekresi’s significance better than that of its founder: Saint Abibos Nekreseli, one of the Thirteen Assyrian Fathers who brought monasticism to Georgia in the 6th century.

Abibos arrived in Georgia from Syria under the leadership of Saint Ioane of Zedazeni, part of a wave of ascetic missionaries who established monasteries throughout the Georgian kingdoms. While his companions founded communities at Shio-Mgvime, David Gareja, and Alaverdi, Abibos was sent to the eastern frontier—to Nekresi, in the hills of Kakheti.

At this time, eastern Georgia was under Persian Sassanid rule. The Persians actively promoted Zoroastrianism, the state religion of their empire, and fire altars burned throughout the region. Georgian Christians faced pressure to abandon their faith and adopt fire worship.

Abibos would have none of it.

According to the chronicle Life of Kartli, Abibos traveled throughout his diocese preaching Christianity and converting not only Georgians but also the mountain tribes across the Alazani River—including the ancestors of modern Dagestanis. His success infuriated Persian authorities.

The confrontation came in the village of Rekhi. Finding Zoroastrian priests forcing Georgian Christians to worship at a fire altar, Abibos walked up to the sacred flame and poured water on it, extinguishing it completely.

The enraged priests seized him, beat him, and reported the outrage to the Persian marzban (governor). As Abibos was transported to face judgment, he received a letter, a blessed bread, and a staff from his friend Saint Simeon the Stylite of the Wonderful Mountain—sent from Antioch after Simeon received a divine vision of Abibos’s coming martyrdom.

Christians offered to help Abibos escape. He refused.

Brought before the marzban, Abibos was asked how he dared raise his hand against the Persian god. His response is recorded in the hagiography: “I did not kill any god; rather I extinguished a fire. Fire is not a god, but a part of nature, created by God. Your fire was burning wood, and a little water was enough to extinguish it. The water turned out to be stronger. Your fury amazes me. Isn’t it humiliating to call something a god which has no soul?”

The marzban ordered his execution. Abibos was beaten, stoned to death, and his body dragged through the streets and cast to the beasts. But the monks of Rekhi stole his body that night and buried it with honor at Samtavisi Monastery. His relics were later transferred to Samtavro Monastery in Mtskheta, where they remain today.

Abibos became a symbol of Georgian Christian resistance to foreign religious domination. His feast day is celebrated on December 12 (Gregorian calendar) or November 29 (Julian calendar).

The Ancient City Beneath the Forest

The hill where Abibos founded his monastery was not empty wilderness. Beneath the trees and undergrowth lay the remains of a once-flourishing city—one that archaeological excavations beginning in 1984 have gradually brought to light.

Ancient sources record that King Parnajom (or Parnavaz, depending on the source) founded a settlement at Nekresi in the 2nd–1st century BC. The town grew to cover approximately 200 hectares, stretching between two hillocks: Nazvrevi Gora on the east (where the monastery now stands) and Samarkhebis Seri (“hill of burials”) on the west.

At its height, Nekresi was a major urban center with multiple religious structures. Archaeologists have uncovered:

The Nekresi Fire Temple: At the foot of Nazvrevi Gora, excavators found the remains of a Zoroastrian shrine that functioned from roughly the 2nd to 4th centuries AD. Its presence confirms that Nekresi was a religiously contested site—exactly the kind of place where the struggle between Christianity and fire worship would have been most intense.

The Chabukauri Basilica: Unearthed in 1998 about 1.5 km northwest of the monastery, this is one of the largest early Christian basilicas in Georgia. Dated to the 4th–5th century, it may be the church that medieval chronicles attribute to King Trdat, son of King Mirian who officially converted Georgia to Christianity. Its discovery challenged the long-held assumption that early Georgian churches were uniformly small, simple structures.

The Dolochopi Basilica: Found in 2012 about 3.5 km east of the monastery, this massive church was built over an even older structure that has been carbon-dated to approximately 387 AD—making it one of the oldest known Christian sites in Georgia, built within decades of the country’s official conversion in 337 AD.

The Nagebebi Winery: On Samarkhebis Seri, archaeologists discovered a large stone winery measuring 20 x 20 meters, confirming that wine production was central to Nekresi’s economy—as it remains in Kakheti today.

These discoveries reveal that Christianity arrived in eastern Georgia earlier and with greater architectural ambition than previously understood. The basilicas at Chabukauri and Dolochopi show connections to building traditions in Syria, Egypt, and the broader Eastern Christian world.

The city of Nekresi declined after Arab invasions in the 8th century. By the Late Middle Ages, the urban settlement had been reclaimed by forest, leaving only the hilltop monastery as a reminder of past greatness. The once-flourishing town disappeared from historical memory until modern archaeology began its rediscovery.

A Dating Controversy Resolved

For decades, scholars believed that a small structure within the monastery complex—the mortuary chapel—dated to the 4th century, making it one of the oldest churches in Georgia. This theory, proposed by the eminent Georgian art historian Giorgi Chubinashvili, held that the chapel was built on the site of a former Zoroastrian shrine, representing Christianity’s literal triumph over fire worship.

However, archaeological excavations conducted from 2008 to 2009 found no evidence of any occupation at the monastery site earlier than the 6th century. The mortuary chapel was definitively redated to the 6th century, contemporary with Abibos’s foundation of the monastery.

This doesn’t diminish Nekresi’s importance—the nearby Dolochopi basilica, with its 387 AD carbon date, confirms that Christianity arrived here very early. But it does mean that the monastery’s visible structures all date from the 6th century or later, built after Abibos established his community here during the Persian period.

The Monastery Complex: Six Centuries of Architecture

The buildings visitors see today span from the 6th to the 16th century, representing nearly a millennium of Georgian ecclesiastical architecture.

The Mortuary Chapel (6th Century)

The oldest surviving structure in the monastery proper, this small church measures only about 4 square meters—intimate enough to feel almost like a prayer closet. Built of rough-hewn stone, it originally served as a funeral chapel where deceased monks were commemorated.

The structure has an unusual design: a high, narrow central section with an apse of similar proportions, flanked by wider and lower side sections that originally opened through horseshoe-shaped vaults. A crypt beneath the building served as a burial chamber. This unconventional plan reflects the experimental nature of early Georgian church architecture, when builders were still developing the forms that would later become standard.

Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (6th–7th Century)

The main church of the monastery is a three-church basilica—a distinctively Georgian type in which the central nave and two side aisles are separated by solid walls rather than columns, creating what are effectively three parallel churches under one roof.

Built of cobblestone and rubble stone, the church measures 17.2 x 12.7 meters. The central nave terminates in a deep sanctuary apse, flanked by rectangular rooms (pastophoria) on either side. The side aisles also end in smaller apses.

The western exterior wall features a remarkable decoration: a huge cross outlined within a flat niche created entirely through the stone-laying technique—a subtle but powerful statement of faith.

Inside, 16th-century frescoes commissioned by King Levan of Kakheti (r. 1518–1574) cover the walls. Though now damaged and blackened by centuries of candle smoke, identifiable subjects include portraits of King Levan and his wife Queen Tinatin on the southern wall, along with scenes of the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, the Dormition, the Nativity of the Theotokos, and the Raising of Lazarus. Above the altar, the Virgin Mary sits enthroned with archangels Michael and Gabriel.

Church of the Archangel Michael (8th–9th Century)

This domed church represents a transitional moment in Georgian architecture—an attempt to combine the three-church basilica form with a central-dome design.

The square interior is topped by a tall, slender drum rising through squinches on the west and horizontal stone slabs on the east. External ambulatories (covered walkways) wrap around the north, south, and west sides, ending in altar niches on the east—a visual echo of a basilica’s side aisles. A polygonal apse projects from the east.

The proportions are striking: the vertical main space, with its narrow, shallow decorative niches, contrasts dramatically with the horizontal stretch of the galleries.

The northern ambulatory, notably darker and more separated from the main space, may have served a specific mortuary function—a place to store the coffins of deceased monks before burial.

The Bishop’s Palace (9th Century)

Adjacent to the main church stands a two-story structure that served as the residence of the Bishop of Nekresi.

The ground floor contains a wine cellar with qvevri (traditional Georgian clay wine vessels) still visible—a reminder that wine production was integral to monastic life. The upper floor provided living quarters for the bishop and monastery administration.

A refectory (dining hall) from the 12th century is attached to the palace’s eastern wall.

The palace’s most striking feature is a grand hall on the ground floor, opened by huge horseshoe-shaped arches—a design that some scholars have compared to medieval German palaces, though the connection is probably coincidental rather than direct influence.

The Defensive Tower (16th Century)

A tall, four-story rectangular tower rises from the middle of the palace complex—added during the reign of King Levan or his successor Alexander II (r. 1574–1605) to provide defense against the increasingly frequent raids from Dagestani mountain tribes.

The tower includes arrow slits in its walls, confirming its military function. From its upper levels, watchmen could survey the valley below and spot approaching threats.

The Diocese and Its Decline

From its foundation until the early 19th century, Nekresi served as the seat of a Georgian bishop (titled “Nekreseli”). The diocese was unusual in that it included not only Georgian territories but also parts of Dagestan—reflecting Abibos’s original mission to convert the mountain peoples across the Alazani.

The monastery flourished during the Kingdom of Kakheti, particularly under kings Levan and Alexander II, who strengthened its fortifications and commissioned new artwork. But the constant threat of Dagestani raids eventually became too much. In 1785, the bishop transferred his see from the exposed hilltop monastery to the relative security of the Church of the Mother of God in the nearby village of Shilda.

After the Russian Imperial takeover of the Georgian Church in 1811, the diocese of Nekresi was abolished entirely, and the monastery itself was dissolved. The buildings fell into disrepair, the monks dispersed, and the ancient site entered a long period of dormancy.

Revival came only after Georgian independence. In 1995, the Georgian Orthodox Church reconstituted the Eparchy of Nekresi. In 2000, monks returned to inhabit the monastery for the first time in nearly two centuries. Between 2008 and 2010, the entire complex underwent systematic archaeological exploration and substantial renovation, restoring it to much of its former appearance.

In 2006, the monastery was granted the status of a National Monument by presidential decree.

The Legend of the Pigs

Nekresi is home to one of the most unusual traditions in all of Eastern Orthodoxy: pig sacrifice.

The story goes that during a raid by Muslim invaders—variously identified as Lezgins (Dagestanis) or Tatars—the local population took refuge inside the monastery. The attackers laid siege, and the situation seemed hopeless.

But the monks had an idea. Among the monastery’s livestock were pigs—animals considered deeply unclean in Islam. The defenders slaughtered the pigs and poured their blood around the perimeter, or (in another version) released starving pigs to charge down the hillside at the attackers.

The sight of pigs was so repulsive to the Muslim raiders that they immediately withdrew.

To commemorate this deliverance, the monastery established a tradition of pig sacrifice—unique in Georgia, where Orthodox Christians typically sacrifice sheep, cattle, or poultry. To this day, during the Nekresoba festival on January 7 (Orthodox Christmas), locals bring pigs to Nekresi for sacrifice and blessing.

Whether the legend is historical fact or folk explanation for an older, perhaps pre-Christian custom, the tradition makes Nekresi unlike any other church in the Orthodox world.

Notable Figures of Nekresi

Beyond Saint Abibos, several important Georgian religious figures served at Nekresi:

Father Ambrosi Nekreseli (18th century): A highly educated theologian and famous orator whose sermons are considered outstanding examples of Georgian homiletics (the art of preaching).

Dositeos Cherkezishvili (18th century): A clergyman and writer who contributed to Georgian religious literature.

Zakaria Mikadze (18th century): Another notable writer and churchman associated with Nekresi.

The Poet-Deacon Moses (19th century): A literary figure who served at the monastery in its final years before dissolution.

Visiting Nekresi Monastery

Location

Nekresi Monastery is located in the Kvareli Municipality of Kakheti, approximately 7 km from the town of Kvareli itself. It sits at an elevation of 480 meters above sea level on the northern slope of the Gombori Ridge, near the village of Shilda.

Getting There

Best of course if to visit it with us during our two day tour in Kakheti.

By Private Vehicle: Drive to the parking area at the base of the hill. Note that you cannot drive your own vehicle to the monastery itself—the final ascent is restricted.

Shuttle Bus: A monastery minibus runs from the parking area to the complex. The fare is minimal (approximately 1 GEL / 50 cents). This is recommended, as it saves energy for exploring the complex itself.

On Foot: A steep walking path leads from the parking area to the monastery. Allow 20–30 minutes for the climb.

Practical Information

Hours: Generally open 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM (hours may vary seasonally; closed Mondays in some reports).

Dress Code: As an active monastery, modest dress is required. Women should cover their heads; both men and women should cover shoulders and knees.

Time Needed: Plan 1.5 to 2 hours for the visit, including the shuttle or walk up, exploration of the complex, and time to absorb the views.

Photography: Generally permitted in the complex, but be respectful around monks and during any services. Flash photography may be restricted inside churches.

What to See

The Panoramic Views: The hilltop location offers sweeping vistas over the Alazani Valley, Georgia’s premier wine-growing region. On a clear day, you can see the snow-capped peaks of the Greater Caucasus rising to the north.

The Mortuary Chapel: The oldest building, with its unusual design and crypt below.

The Church of the Dormition: The main church with its 16th-century frescoes. Look for the cross outlined in the western exterior wall.

The Church of the Archangel: An architectural experiment combining basilica and domed church forms.

The Bishop’s Palace and Wine Cellar: A glimpse into medieval monastic life, including the qvevri wine vessels that connect Nekresi to Kakheti’s ancient winemaking tradition.

The Defensive Tower: Climb if possible for even better views.

Combining with Other Sites

Nekresi sits in the heart of Kakheti, Georgia’s wine country, surrounded by other attractions:

Gremi Monastery and Fortress (25 minutes by car): A striking 16th-century complex built by King Levan—the same king who commissioned Nekresi’s frescoes. Includes the Church of the Archangels, a three-story palace-bell tower, and fortress walls.

Ilia Chavchavadze House-Museum (20–25 minutes): The birthplace of one of Georgia’s greatest writers and national heroes, including the ancestral tower, wine cellar, and a three-story museum.

Ilia’s Lake / Kvareli Lake (20 minutes): A beautiful mountain lake at 1,100 meters elevation, popular for picnicking and swimming in warmer months.

Kvareli Wine Tunnel (15 minutes): A 7.7 km tunnel carved into the mountainside that maintains perfect wine-aging conditions. Tours and tastings available.

Telavi (30–40 minutes): The regional capital of Kakheti, with the Batonistsikhe royal residence, plane tree courtyard, and numerous wine cellars.

Alaverdi Cathedral (40 minutes): One of the tallest medieval churches in Georgia, founded by another of the Thirteen Assyrian Fathers.

Frequently Asked Questions

How old is Nekresi Monastery? The monastery was founded in the 6th century by Saint Abibos Nekreseli. The oldest surviving structure in the monastery complex (the mortuary chapel) also dates to the 6th century. However, archaeological excavations have uncovered much older Christian churches in the surrounding area, including the Dolochopi basilica with remains carbon-dated to 387 AD.

Is the small church at Nekresi from the 4th century? This was long believed to be true, but archaeological excavations in 2008–2009 disproved this dating. The mortuary chapel is now firmly dated to the 6th century. The 4th-century churches of Nekresi (Chabukauri and Dolochopi basilicas) are located in the surrounding area, not within the monastery complex itself.

Who was Saint Abibos? Abibos was one of the Thirteen Assyrian (Syrian) Fathers who brought monasticism to Georgia in the 6th century. He was martyred by the Persians for extinguishing a sacred Zoroastrian fire. His relics are preserved at Samtavro Monastery in Mtskheta.

What is the Nekresoba festival? A unique celebration held on January 7 (Orthodox Christmas) featuring pig sacrifice—the only Georgian Orthodox church where this tradition exists. It commemorates a legend in which pigs helped repel Muslim invaders.

Can I drive to the monastery? No. Private vehicles must park at the base of the hill. A monastery shuttle bus runs to the complex, or you can walk up the steep path (20–30 minutes).

Is Nekresi still an active monastery? Yes. Monks returned to Nekresi in 2000 after nearly two centuries of abandonment, and the monastery is part of the Eparchy of Nekresi within the Georgian Orthodox Church.

What should I combine Nekresi with? The monastery pairs well with other Kakheti attractions: Gremi (same era, same king), Alaverdi (another Assyrian Father monastery), and the numerous wineries of the region.

How much time do I need? Allow 1.5 to 2 hours for the monastery itself, plus travel time. If combining with the shuttle ride and taking time for views, two hours is comfortable.

The Weight of History

Standing at Nekresi, looking out over the Alazani Valley toward the Caucasus peaks, you’re standing on ground where empires clashed, faiths collided, and individuals made choices that shaped a nation’s identity.

Abibos chose martyrdom over compromise. The monks chose pigs over surrender. Archaeologists have chosen to dig, and their discoveries are revealing that Christianity sank deeper roots here, earlier, than anyone previously imagined.

Below your feet, beneath centuries of forest growth, lie the ruins of a city that rivaled Mtskheta in importance. Around you stand buildings that span a millennium of Georgian faith. And in the silence of the hilltop, broken only by birdsong and the bells of the monastery, you can still sense why this place mattered—and why it still does.