Wine Tours in Georgia: What 8,000 Years of Winemaking Actually Tastes Like

The first time I watched a winemaker pry open a qvevri after six months underground, I understood something no book about Georgian wine had ever conveyed. The smell that rises from those buried clay vessels isn’t just wine. It’s earth, autumn, time itself. The amber liquid inside looked nothing like any white wine I’d ever seen — deep gold, almost copper, with a texture you could feel before it touched your lips.

Most travellers who come to Georgia for wine expect something like Tuscany or Napa. What they find is something far stranger and more profound. In 2017, archaeologists at a site called Gadachrili Gora in southern Georgia found pottery shards with grape residue dating to 6000 BC — the oldest evidence of winemaking ever discovered anywhere on Earth. But that’s the statistic. The lived reality is this: Georgia never stopped making wine. The same clay vessels, the same methods, the same grape varieties — for eight thousand years, without interruption. No other wine country on earth can say that.

And unlike the famous wine regions of France or Italy, Georgian winemaking hasn’t been commercialised into a polished tourist product. When you visit a family winery in Kakheti, you’re sitting in someone’s home. The winemaker pouring for you is often the same person who pruned the vines, stomped the grapes, and sealed the qvevri. The feast that follows isn’t a marketing exercise — it’s how Georgians have welcomed guests for millennia.

I’ve been running wine tours across Georgia for over fifteen years, and I still find wineries that surprise me. This guide is what I wish someone had given me before my first Georgian wine experience: not a textbook, but a map to the things that matter.

What Makes Georgian Wine Different: The Qvevri

If you’ve ever had a so-called “orange wine” at a natural wine bar in London or New York, you’ve tasted a style that Georgia invented eight thousand years ago. The qvevri (ქვევრი) is a large egg-shaped clay vessel, sometimes holding over 3,000 liters, buried in the ground up to its rim. Grapes go in whole — juice, skins, seeds, sometimes stems — and the earth does the rest. No temperature-controlled stainless steel. No commercial yeast. No oak barrels. Just clay, gravity, and time.

The result tastes like nothing in the European wine tradition. White wines come out amber-gold, tannic, rich with dried apricot and walnut and honey. Reds emerge darker and wilder than their European equivalents. In 2013, UNESCO inscribed the qvevri method as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity — the only winemaking technique in the world to hold that status.

What the UNESCO certificate doesn’t capture is the atmosphere of a marani — a Georgian wine cellar. The best ones feel almost sacred. Dim light. Cool air. Rows of qvevri flush with the stone floor, their clay lids sealed with beeswax. In many families, the marani is considered the holiest room in the house, more important even than the church.

On our organic wine tour in Kakheti, guests taste directly from qvevri at three family wineries. It’s one thing to read about this method; it’s another to kneel on a cellar floor while a winemaker uses a hollowed gourd to scoop wine from a vessel his grandfather built.

Amber Wine: Georgia’s Gift to the World

The wine world’s current obsession with orange wine is essentially a rediscovery of something Georgians never forgot. In conventional winemaking, white grapes are pressed, and the juice is fermented without skins. In Georgia, white grapes ferment WITH their skins for five to six months inside the qvevri. The skins give the wine its color — ranging from straw-gold to deep amber — and its tannic structure, which is completely absent from conventional whites.

The taste is polarizing, which is part of the appeal. Your first sip of a Kakheti amber Rkatsiteli might remind you of sherry, or dried apricot, or even tea. There’s a savory, almost umami quality that makes it pair brilliantly with food — something light whites struggle with. Georgian winemakers sometimes laugh when Europeans call these “orange wines” as though it’s a new category. In Georgia, this is simply how white wine is made.

Not all Georgian whites are amber. In western regions like Imereti, winemakers use shorter skin contact — one to two months instead of five or six — producing lighter, brighter wines from grapes like Tsolikouri and Tsitska. On our Western Georgia wine tour, you taste both traditions side by side, which is the fastest way to understand the range of Georgian winemaking.

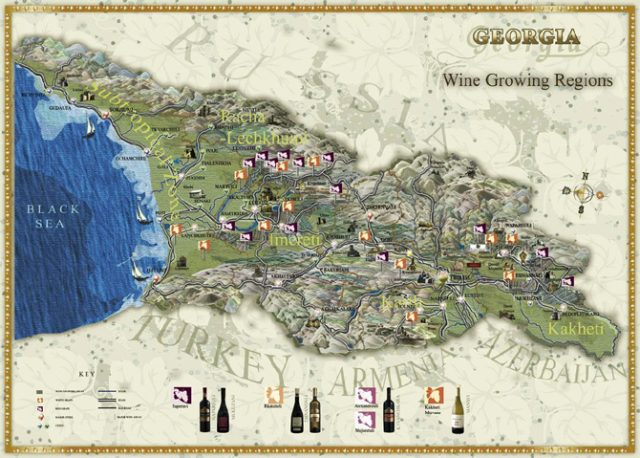

Where to Drink: Georgia’s Wine Regions Through the Eyes of a Local

Kakheti: Where Most Wine Tours Begin (and Why)

About seventy percent of Georgia’s wine comes from Kakheti, the eastern region cradled between the Alazani River valley and the Greater Caucasus. It’s the region most visitors see first, and for good reason — the concentration of wineries here is extraordinary, from one-family operations making 500 bottles a year to estates producing hundreds of thousands.

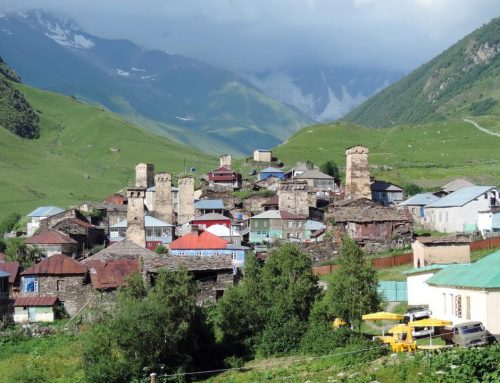

The landscape itself shapes the experience. Driving over the Gombori Pass from Tbilisi, the terrain shifts from dry scrubland to lush green valley in the span of twenty minutes. Suddenly there are vineyards everywhere, and behind them, the snow line of the Caucasus. It’s the kind of backdrop that makes even average wine taste better

The wines to seek out here are Saperavi — Georgia’s flagship red, so deeply colored it can stain your teeth for an afternoon — and Rkatsiteli, the white grape that produces both conventional crisp wines and the famous amber style. But the real discoveries come from lesser-known grapes like Kisi and Khikhvi, which small producers are reviving after decades of neglect. These are wines you genuinely cannot find outside Georgia.

For a focused introduction, our organic wine tour in Kakheti visits three family estates in a single day: Beqa Jimsheladze’s Vellino winery, Jenny’s Okro’s Wines in Sighnaghi, and a qvevri master’s workshop near Telavi. You’ll taste twelve to fifteen wines and have lunch overlooking the Alazani Valley.

Western Georgia: The Wines Most Visitors Miss

If Kakheti is Georgia’s Burgundy, then Imereti and Racha-Lechkhumi are its Jura — smaller, quirkier, and beloved by people who know. The winemaking philosophy here is fundamentally different from eastern Georgia. Shorter skin contact produces lighter, more aromatic whites. The climate is subtler, the producers fewer, and the wines harder to find.

Racha-Lechkhumi, tucked into the mountains northwest of Kutaisi, produces what might be Georgia’s most precious wines. Khvanchkara — a naturally semi-sweet red made from Aleksandrouli and Mujuretuli grapes — comes from a microzone so small that total production is tiny. Then there’s Usakhelouri, from a grape so rare it may be the most expensive Georgian wine in existence. You will not find these in a shop in Tbilisi, let alone abroad.

Our five-day Western Georgia wine tour is the only way we know to properly experience these regions. Day trips from Tbilisi don’t reach here — the distances require overnights, which is actually part of the charm. Evenings in Racha feel like stepping back in time.

Kartli: The Region Hiding in Plain Sight

Kartli surrounds Tbilisi, which means most visitors drive through it without stopping. That’s a mistake. The Mukhrani Valley produces Chinuri, a white grape that makes one of Georgia’s few traditional sparkling wines (called Atenuri, from the Ateni Gorge). And Château Mukhrani — a beautifully restored nineteenth-century estate — offers one of the most polished winery visits in the country.

But the real reason to stop in Kartli is Iago Bitarishvili. His tiny operation in Chardakhi village produces natural Chinuri wines that have become cult favorites among wine writers globally. Visiting Iago is an education in what one person with strong opinions and old vines can achieve.

The Supra: Why Georgian Wine Is Inseparable from Georgian Feasting

You cannot understand Georgian wine without understanding the supra. In most wine cultures, wine accompanies food. In Georgia, wine, food, and ceremony are a single indivisible experience — and the supra is the format.

A supra is led by a tamada, a toastmaster who guides the table through a sequence of toasts — to God, to Georgia, to guests, to parents, to children, to friendship, to love. These aren’t the thirty-second glass-raises you know from Western dinners. A tamada’s toast can last five minutes, weaving together philosophy, humor, history, and genuine emotion. The table listens. Then everyone drinks. Then the food is replenished — because an empty table is a source of genuine shame in Georgia.

For visitors, the supra can be overwhelming. The toasts are in Georgian (your guide translates). The food keeps coming. The wine never stops. The singing starts — Georgian polyphonic folk music, where three or four voices lock into harmonies that UNESCO also considers world heritage. It’s loud and emotional and deeply communal.

My advice to visitors: eat steadily, drink moderately, listen carefully, and say yes when offered an alaverdi — a chance to expand on the tamada’s toast with your own words. Nobody expects eloquence. They want sincerity. And if you raise your glass and say “Gaumarjos!” with feeling, you’ll have friends for life.

Most of our wine tours include supper-style meals at family wineries. It’s the one experience that every guest, without exception, tells us was the highlight of their trip.

Rtveli: The Harvest Season That Turns Georgia Into One Big Celebration

If you can time your visit to Georgia for September or October, do it. Rtveli (რთველი) — the grape harvest — is when the entire country seems to shift into a higher gear. Families return to ancestral vineyards. Office workers take harvest leave from their jobs. The roads to Kakheti fill with trucks carrying grapes, and the air in wine villages smells of fermentation.

Unlike harvest season in France or California, which is largely a professional operation behind closed doors, rtveli in Georgia is participatory and social. Neighbors help each other pick. Friends drive in from Tbilisi. Children stomp grapes in wooden troughs while their grandmothers make churchkhela — walnut strings dipped in thickened grape juice, the traditional harvest snack.

Several of our partner wineries open their doors to visitors during rtveli. You can pick grapes, help fill qvevri, and join the harvest supra that closes each day. Be warned: you will get grape juice on your clothes, you will eat too much, and you will almost certainly be invited back next year.

The exact harvest dates shift each year depending on weather, but Kakheti typically peaks in late September to mid-October. Book early — harvest tours are the first to fill. Our tours page has current availability and seasonal options.

525 Grapes You’ve Never Heard Of

Georgia has over 525 indigenous grape varieties, more than any other country. About fifty are in commercial production. But numbers don’t capture what makes this special. What matters is that these grapes exist NOWHERE else. You cannot buy a bottle of Kisi or Otskhanuri Sapere in the United States or Germany. They are genetically unique to Georgia.

If you visit one region, you’ll encounter two grapes above all others. Saperavi is the red: deeply pigmented (it’s a teinturier grape, meaning even the flesh is red), tannic, dark-fruited, and age-worthy. Think of the intensity of Malbec with the structure of Syrah, and you’re in the neighborhood. Rkatsiteli is the white: versatile, widely planted, and capable of producing wildly different wines depending on whether it’s made in stainless steel (crisp, appley) or qvevri (amber, tannic, complex).

Beyond those two, the grape that consistently impresses visitors on our tours is Kisi — a white variety that produces layered, aromatic wines with apricot and spice notes, especially when fermented in qvevri. Winemakers like Beqa at Vellino and Jenny at Okro’s Wines are doing extraordinary things with it.

For red wine lovers willing to venture beyond Kakheti, seek out Otskhanuri Sapere from Imereti (dark, tannic, serious) and Aleksandrouli from Racha (softer, raspberry-scented, elegant). These are among Georgia’s most exciting wines, and they barely exist outside their home regions.

For a detailed breakdown of grape varieties by region with tasting notes, see our complete Georgian wine tours guide.

When to Go: A Season-by-Season Insider’s Take

September–October (Harvest): The obvious answer, and the right one. Rtveli season is Georgia at its most alive. Expect warm days, harvest activities at every winery, and an energy in the wine regions that doesn’t exist at other times. The downside: everyone else knows this too. Book early.

May–June (Qvevri Opening): My personal favorite season for wine tourism. This is when winemakers open qvevri sealed the previous autumn, and the new vintage wines are tasted for the first time. The vineyards are green, the weather is perfect, and you’ll have wineries largely to yourself. Tbilisi’s Wine Festival usually falls in May.

November–March (Off-Season): Underrated. Winter wine touring means empty cellars, unhurried conversations with winemakers, and the chance to taste barrel samples and experimental batches that busy-season visitors never see. Kakheti under snow, with smoke rising from village chimneys and the Caucasus range in white, is its own kind of beautiful.

July–August (Summer): Hot in Kakheti — regularly above 35°C. The vineyards are loaded with fruit but cellar visits provide welcome cool. If you’re combining wine with beach time in Adjara or hiking in Svaneti, summer works well as part of a broader Georgia itinerary.

See also When is the best time for Georgia.

What to Actually Expect on a Georgian Wine Tour

Georgian wine tours are not Napa Valley. Forget sleek tasting rooms with printed menus and $30 pours. At a family winery in Kakheti, you’re likely to be greeted by the winemaker’s mother, handed a glass of chacha (grape brandy) before you’ve put your bag down, and led into a cellar that doubles as the family’s pride and living heritage.

Tastings are generous — sometimes alarmingly so. Spitting is technically fine but culturally unusual; if you need to pace yourself, simply don’t finish every glass. Food is always present, because the idea of drinking without eating is borderline offensive in Georgia. At minimum, expect bread, cheese, and churchkhela alongside your wines. At many family wineries, a full meal materializes even if you didn’t plan for one.

Chacha will appear. It always does. The family’s homemade grape brandy, often between 50% and 65% alcohol, offered with pride. A small sip is respectful; declining is also fine. Just know it’s coming.

The conversations are real. Georgian winemakers are not trained hospitality professionals reciting scripts. They’re farmers, philosophers, and storytellers. Ask about their vines and you’ll get a twenty-minute family history. Ask about politics and you might not leave until dark.

Practical Notes

Cost Reality Check

Georgia is affordable for wine tourism. A tasting at a family winery typically costs 20–50 GEL ($7–18). A full-day private wine tour with driver, guide, tastings, and lunch runs $170–$200 per person. Compare that to Bordeaux or Tuscany and the value is staggering. Bottles at wineries cost $5–30 for wines that would be priced three to five times higher if they came from France.

Don’t Drive Yourself

Georgian police enforce drunk driving laws strictly, and generously poured tastings across three wineries will put you over the limit. A private tour with a dedicated driver isn’t just convenient — it’s essential. All of our wine tours include comfortable transport and an experienced driver who knows the backroads to the best cellars.

Buying Wine to Take Home

Buy at wineries, not shops. The small-production wines that make Georgian wine special are often only available on-site. Most winery bottles are well under $20. Pack them in checked luggage (wrap in clothes, check airline regulations) or ask your guide about shipping options for larger purchases.

Start Planning

Georgia’s wine story is eight thousand years old, and it’s still being written — by families in stone-walled cellars, by young winemakers reviving forgotten grapes, by guests who arrive curious and leave converted. Whether you have one day or ten, there’s a wine experience here that will change how you think about wine.

Browse our wine tours to find the right fit, or contact us to build a custom itinerary around your interests. We’ve been doing this a long time, and we love matching the right travelers with the right wineries.

Gaumarjos!