Martvili monastery

On a hilltop where ancient Georgians once worshipped a sacred oak and sacrificed to fertility gods, seventh-century Christians built a church modeled on Jvari—and created what would become the most powerful educational center in western Georgia. Here Giorgi Chkondideli taught the boy who would become David the Builder, greatest of Georgian kings.

Introduction: The Monastery That Educated a King

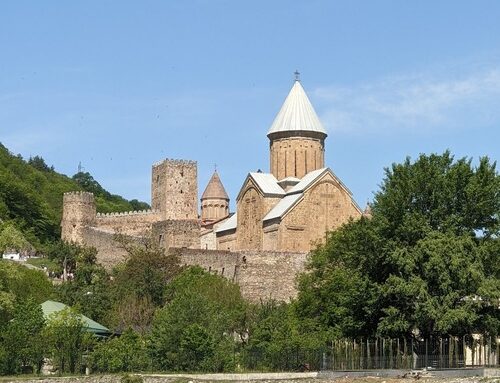

Martvili Monastery (მარტვილის მონასტერი), also known as Chkondidi Cathedral, rises from the highest hill above the town of Martvili in Samegrelo, commanding views across the vast Kolkheti lowlands to where Imereti begins. From this promontory, you can see almost all of western Georgia stretching to the horizon—a view that made this site strategically vital and spiritually significant for over a thousand years.

But Martvili’s importance transcends geography. This monastery educated Giorgi Chkondideli, who became the teacher, advisor, and kingmaker behind David IV “the Builder” (1089-1125)—the greatest monarch in Georgian history. The position Giorgi held, Chkondidel-Mtsignobartukhutsesi (combining the bishopric of Chkondidi with the office of royal chancellor), made him second only to the king in secular affairs and second only to the Catholicos-Patriarch in religious matters.

The monastery’s story spans from pagan oak worship through infant sacrifice to Christian triumph, from medieval scholarship to Bolshevik desecration, from abandonment to revival. Today, it operates as both a functioning monastery and a testament to Georgia’s enduring faith.

Quick Overview:

- Full name: Martvili-Chkondidi Monastery

- Original construction: Late 7th century

- Major reconstruction: 10th century under King Giorgi II

- Location: Village of Martvili, Martvili Municipality, Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti region

- Dedication: Assumption of the Virgin Mary (Dormition)

- Name meaning: “Martvili” = Greek for “martyr”; “Chkondidi” = Megrelian for “Big Oak”

- Distance from Kutaisi: ~45 km (1 hour)

- Distance from Tbilisi: ~280 km (5 hours)

- UNESCO Status: Not listed, but culturally significant

- Current status: Active monastery (St. Andrew the First-Called Monastery and St. Nino Nunnery)

The Sacred Hill: From Pagan Oaks to Christian Triumph

The Ancient Oak Cult

Before Christianity reached this hilltop, the Megrelian people venerated it as a pagan sacred site. An enormous ancient oak tree stood here—a chkoni in the Megrelian language—worshipped as an idol of fertility and prosperity.

The practices at this site were dark. According to historical sources, infants were sacrificed beneath the oak as offerings to the gods. The tree itself was considered divine, and the hilltop served as a major pagan cultural center for the region.

Oak worship was widespread in ancient western Georgia. The Megrelian name “Chkondidi” (დიდი ჩქონი—”Big Oak”) preserves this pre-Christian heritage, reminding visitors that the monastery stands on soil once consecrated to very different deities.

Saint Andrew’s Mission

According to Georgian Orthodox tradition, Saint Andrew the Apostle traveled through the region of Samegrelo in the first century AD, preaching Christianity and converting pagans. When Christianity finally triumphed in Georgia (traditionally dated to 337 AD), the old practices at sacred sites like this were suppressed.

The ancient oak was cut down—symbolically ending the fertility cult. In its place, a church was built upon the very roots of the tree. The first church here was dedicated to Saint Andrew, honoring his role in bringing Christianity to the region.

The 7th-Century Church

The original Martvili Cathedral was constructed in the late 7th century (first half of the 7th century according to some scholars). Its architects looked to the greatest Georgian church of that era for inspiration: the Jvari Monastery near Mtskheta, which had been completed around 604 AD.

Like Jvari, the original Martvili church featured a “free cross” configuration—a tetraconch design with four apses creating a cross shape. However, the Martvili architect applied creative innovations, including:

- A reduced dome size with enlarged internal corner niches

- Overhanging arches instead of traditional trompes (squinches)

- A five-faceted apse exterior rather than the traditional three-faceted design

- Decorative elements arranged in a consecutive belt around the upper apse sections

These innovations gave the church a distinctive lightness, distinguishing it from the more “solid and calm” churches of eastern Georgia.

The 10th-Century Reconstruction and Rise to Power

Destruction and Rebuilding

The original 7th-century church suffered severe damage during the Arab-Turkish invasions that plagued Georgia for centuries. By the 10th century, little remained of the first structure.

King Giorgi II of Abkhazia (ruled c. 922-957) ordered the complete reconstruction of the cathedral. The new church was significantly larger and more impressive than its predecessor. Giorgi II also elevated Martvili’s status by declaring it an episcopal see—the seat of a bishop.

The reconstructed cathedral retained the general cruciform layout of its predecessor but incorporated changes, including:

- A dome of later design

- “Rectified” (flattened) longitudinal façades

- A western porch featuring an impressive rising image of the Blessing Christ

- Updated facing on the exterior

The Chkondidi Episcopate

The bishopric of Chkondidi quickly became one of the most influential religious positions in western Georgia—second only to the Catholicos-Patriarch in the Georgian Church hierarchy. The bishops of Chkondidi wielded enormous power, not just spiritually but politically.

This power would reach its apex in the 11th-12th centuries, when the position was merged with the office of royal chancellor, creating a dual role that shaped Georgia’s golden age.

Giorgi Chkondideli: The Teacher Who Made a King

The Man Behind David the Builder

Giorgi Chkondideli (“George of Chkondidi”) was born in the mid-11th century and rose to become bishop of Chkondidi at Martvili Monastery. He was described as a man of extraordinary learning, political acumen, and spiritual authority.

When the young Prince David (later David IV “the Builder”) needed education, Giorgi Chkondideli became his teacher and mentor. At Martvili Monastery, in cells that visitors can still see today, Giorgi shaped the mind of the boy who would become Georgia’s greatest king.

The education Giorgi provided was comprehensive:

- Theology and religious knowledge

- Languages (David later read Persian poetry and the Quran)

- History and governance

- Military strategy

- Astronomy and sciences

David’s chronicler would later write that the king “knew the deeds better than any other king” because he was enthralled with theology, astrology, and history, bringing his books with him even on military campaigns.

The 1089 Transition of Power

In 1089, when Georgia was devastated by Seljuk Turkish invasions and King Giorgi II had failed to restore order, a palace revolution occurred. The 16-year-old Prince David was elevated to the throne, and his father was forced to abdicate.

Historians believe Giorgi Chkondideli was among the leaders of this transition of power—perhaps even its mastermind. Whether it was a formal coup or pressure that compelled George II to step aside, David’s former teacher helped place him on the throne.

The Chkondidel-Mtsignobartukhutsesi

At the Council of Ruis-Urbnisi in 1103, King David IV enacted one of the most significant reforms in Georgian history. He merged two powerful offices:

- Mtsignobartukhutsesi (მწიგნობართუხუცესი)—the royal chancellor, essentially the prime minister

- Bishop of Chkondidi—the most powerful episcopal see after the Catholicos-Patriarch

The new combined position, Chkondidel-Mtsignobartukhutsesi, made its holder:

- First person in the kingdom after the king

- First person in the Church after the Catholicos-Patriarch

- Head of the highest judicial body (saadzho kari)

- Called the king’s “vizier” and “father”

Giorgi Chkondideli was confirmed in this position—essentially becoming the second most powerful person in Georgia. He alone had the right to propose matters for the king’s consideration; other officials could speak only when asked.

Death in Service

Giorgi Chkondideli served David the Builder faithfully for decades. When David needed to recruit Qipchak (Kipchak) warriors from the northern Caucasus to form a standing army, Giorgi accompanied the king on the diplomatic mission to Ossetia.

It was there, in the northern Caucasus, that Giorgi Chkondideli died—”an adviser to his master and participant in his great works and victories,” as the chronicles describe him. King David declared forty days of mourning for the kingdom.

The position Giorgi created continued after his death. His successors as bishops of Chkondidi were automatically appointed royal chancellors, and Martvili Monastery remained central to Georgian governance until the kingdom’s decline.

The Medieval Cultural Center

Crisperia: The Scriptorium

Martvili Monastery served as far more than a place of worship. It became one of western Georgia’s most important educational and cultural centers.

The monastery housed a Crisperia—a scriptorium where monks copied, translated, and created literary works. Books were translated into Georgian from Greek, Arabic, and other languages. Original theological and literary works were composed. Religious manuscripts were copied for distribution throughout western Georgia.

This scholarly tradition helped preserve Georgian language and literature during centuries of invasion and instability.

The Burial of King Bagrat IV

According to the Georgian Chronicles, King Bagrat IV (ruled 1027-1072) was buried at Martvili Monastery. Bagrat IV is remembered for appointing Giorgi Mtatsmindeli (a different Giorgi from Chkondideli) as chair of Chkondidi, further cementing the monastery’s connection to Georgia’s intellectual elite.

The presence of a royal burial enhanced Martvili’s prestige and drew pilgrims from across Georgia.

Architecture and Art

The Main Cathedral

The Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (also called the “Blessed Virgin Repose Cathedral”) is the main building of the complex. Though reconstructed multiple times, it retains the “free cross” configuration inspired by Jvari Monastery.

Architectural features:

- Cross-domed design with the dome resting on large columns

- High arched vaults creating an impressive interior volume

- Western porch with a striking image of the Blessing Christ on the pediment

- Five-faceted apse exterior

- Decorative belt of rising elements around the upper apse

The church suffered reconstruction over the centuries, so its current appearance differs from the original 7th-century design. The dome, façades, and facing are all from later periods (primarily 10th century and after).

The Frescoes

Martvili’s interior preserves frescoes spanning the 13th through 17th centuries—some of the highest quality medieval craftsmanship in Georgian history.

Notable paintings include:

- 14th-century sanctuary paintings—scenes from the Old Testament and saints

- 16th-18th century apse decorations

- A famous 17th-century Virgin on the apse ceiling

- Portraits of the Dadiani princes—rulers of Samegrelo who became the monastery’s patrons

- Fragments of 13th-century frescoes alongside small sections of preserved mosaic

The Dadiani family portraits are particularly significant. These aren’t stylized religious figures but actual post-Renaissance-style portraits—some of the earliest examples of secular portraiture in Georgian art. They depict the Grand Princes of Samegrelo, members of the House of Dadiani who ruled the region from the 14th to 19th centuries.

One exceptional Byzantine artist’s work survives here: Cyrus Emanuel Eugenicos, invited from Constantinople by Vamek Dadiani (ruled 1384-1396), created frescoes that are the only known surviving examples of art from the Byzantine Palaeologian dynasty with a date and artist’s signature.

The Chikvanebi Church

North of the main cathedral stands a smaller, two-storied domed church known as the Church of Chikvanebi (or Holy Christmas Cathedral). Based on its dome ornamentation and apse arcade treatment, scholars date this structure to the early 11th century.

This smaller church likely served specialized liturgical functions and may have accommodated overflow from the main cathedral during major festivals.

The Stylite Tower

West of the main temple stands one of Martvili’s most unusual structures: a tall tower crowned with a small single-nave church adorned with carved fretwork.

This was not merely a bell tower but a dwelling place for hermit monks—stylites who lived ascetic lives atop the pillar, following the ancient Christian tradition of pillar-dwelling that originated with St. Simeon Stylites in 5th-century Syria.

The last stylite monk (pillarist) lived at Martvili as recently as the early 20th century—making this one of the latest documented examples of the practice anywhere in Christianity.

The Dadiani Connection

Princes of Samegrelo

The House of Dadiani ruled the Principality of Samegrelo from the 14th century until Russian annexation in 1857. Throughout this period, they were principal patrons of Martvili Monastery.

The Dadianis commissioned frescoes, funded repairs, and maintained the monastery as a center of Samegrelo religious and cultural life. Several Dadiani princes and family members are buried at Martvili, including:

- Levan V Dadiani (ruled 1804-1840) and his wife Martha

- David Dadiani (ruled 1840-1853)

The ruins of an old Dadiani palace can be found just outside the cathedral walls, evidence of the close relationship between the princely family and the monastery.

Bishop Gregory (Dadiani)

In the second half of the 19th century, Bishop Gregory (Dadiani)—a member of the princely family—oversaw construction of an episcopal palace west of the main church. This building demonstrated that even after Russian annexation ended the principality’s independence, the Dadiani family maintained their connection to their ancestral spiritual center.

Soviet Closure and 1998 Revival

The Soviet Period

Like virtually all Georgian religious institutions, Martvili Monastery was closed and suppressed during the Soviet era. Monks were dispersed, religious services ceased, and the buildings fell into disrepair.

The Lavra of the Fathers (fathers’ monastery) that had operated since the 19th century was shut down in the 1920s. For decades, the ancient complex stood abandoned—one of countless Georgian holy sites suffering under atheist rule.

Patriarch Ilia II’s Revival

In 1998, with the blessing of Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia, Martvili was restored as an active monastery. The revival established:

- St. Andrew the First-Called Father’s Monastery (men’s monastery)

- St. Nino Nunnery (convent)

Monks and nuns returned to live and worship where their predecessors had served for over a millennium. A patriarchal residence was constructed in the vicinity of the church, and monastic life resumed.

The Chapel-Museum

In one of the most prominent locations within the complex—the former royal treasury room from the late Middle Ages—a chapel-museum has been opened. This small museum preserves relics from various historical periods, allowing visitors to appreciate Martvili’s long history.

The museum is overseen by the monastery’s clergy and represents an effort to preserve and display the site’s heritage while maintaining its active religious function.

Visiting Martvili Monastery: Complete Practical Guide

Location

Martvili Monastery stands on a high hill directly above the town of Martvili in the Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti region of western Georgia. The monastery overlooks the valleys of the Tskhenistskali and Abasha rivers.

GPS Coordinates: 42.4567° N, 42.3789° E

Getting There

From Kutaisi (45 km, ~1 hour):

- Head west toward Senaki on the main highway

- Turn north toward Martvili before reaching Senaki

- Follow signs to the monastery

- A cable car from the town center also provides access

From Tbilisi (280 km, ~5 hours):

- Take the main highway west to Kutaisi

- Continue toward Senaki and Martvili

- Combined day trip possible but long; overnight recommended

From Zugdidi (40 km, ~45 minutes):

- Head south toward Martvili

- Often combined with visits to Dadiani Palace in Zugdidi

By Public Transport:

- Marshrutkas run to Martvili from Kutaisi and Zugdidi

- From Martvili town, you can walk up the hill or take a taxi

- The cable car from town center offers an alternative

Access Options

By road: A paved road leads from Martvili town center to the monastery gates.

By cable car: A convenient option that saves the uphill walk and offers panoramic views during the ascent.

What to See

At the Monastery:

- Main Cathedral (Assumption of the Virgin)—examine the architecture and frescoes

- Chikvanebi Church—the smaller 11th-century structure

- Stylite Tower—where the last pillar-dwelling monk lived in the early 1900s

- Chapel-Museum—relics from various historical periods

- Dadiani Palace ruins—outside the walls

- Views—spectacular panoramas across Samegrelo and Imereti

Spiritual Significance:

- Active services in the main cathedral

- Candle lighting

- Prayer before icons

- The cell where Giorgi Chkondideli taught King David the Builder

Monastery Shop

On the path up to the monastery, visitors can stop at a small shop run by the nuns, selling:

- Embroidery and handicrafts

- Candles

- Religious souvenirs

- Products made by the monastic community

Dress Code

As an active Orthodox monastery:

- Women: Cover head, shoulders, and knees; long skirt or dress preferred

- Men: Long trousers, shoulders covered

- Remove hats inside churches

- Behave quietly and respectfully

- Photography may be restricted in some areas—ask permission

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (April-June): Pleasant weather, green landscapes

- Summer (July-August): Peak season, warmer temperatures

- Autumn (September-October): Beautiful colors, fewer tourists

- Winter: Accessible but quieter; can be cold and damp

Time Needed

- 45 minutes-1 hour: Basic visit to main cathedral and grounds

- 1.5-2 hours: Thorough exploration including museum and all buildings

- Half day: Combined with Martvili Canyon

Combining with Martvili Canyon

Martvili Monastery and the famous Martvili Canyon are located just minutes apart, making a combined visit easy and rewarding.

About Martvili Canyon

Martvili Canyon (also called Gachedili Canyon) is a spectacular natural monument carved by the Abasha River. The canyon features:

- Walls 20-70 meters high

- 2.4 km length

- Turquoise-blue waters

- Multiple waterfalls including a 25-meter cascade

- Moss-covered limestone cliffs

The canyon was a favorite retreat of the Dadiani princes—the same family who patronized Martvili Monastery.

Canyon Practical Information (2025)

Entrance Fees:

- Adults (foreign): ~17-20 GEL

- Children (6-18): ~5.50 GEL

- Georgian residents: ~10-12 GEL

- Children under 6: Free

Boat Ride:

- Additional 15-20 GEL

- Duration: ~15-20 minutes

- Minimum height: 1 meter

- Highly recommended for the best canyon experience

Opening Hours:

- Variable by season (typically 10am-6pm, extended summer hours until 11pm)

- Night illumination available in summer

- Closed during heavy rain or snow

Tips:

- Wear comfortable, non-slip shoes

- Bring a light jacket (it’s cool in the canyon)

- Arrive early or at lunch to avoid crowds

- Allow 1-1.5 hours for full visit

Suggested Combined Itinerary

Half-Day from Kutaisi: Morning: Martvili Monastery (1-1.5 hours) → Martvili Canyon (1-1.5 hours) → Return to Kutaisi

Full Day from Kutaisi: Morning: Martvili Monastery → Martvili Canyon → Lunch in Martvili → Prometheus Cave or Okatse Canyon → Return to Kutaisi

Full Day from Zugdidi: Dadiani Palace Museum → Martvili Monastery → Martvili Canyon → Lunch → Return to Zugdidi

Other Nearby Attractions

Dadiani Palace Museum (Zugdidi)

The Dadiani Palaces Historical and Architectural Museum in Zugdidi was the main residence of the Dadiani princes. The museum contains:

- Over 41,000 items

- One of Napoleon’s four death masks (acquired through Princess Salome Dadiani’s marriage to Napoleon’s nephew Achille Murat)

- Medieval manuscripts

- Icons and religious objects

- European weapons collection

- Botanical garden

Nokalakevi

The ancient fortress of Nokalakevi (also called Archaeopolis) was once the capital of the Egrisi Kingdom. Some scholars identify it as the legendary city of Aia, where the Argonauts sought the Golden Fleece. The site includes:

- Ancient fortress walls

- Archaeological museum

- Ruins spanning the 4th-6th centuries

Salkhino Palace

The Salkhino Dadiani Palace, the summer residence of the Dadiani princes, is located near Martvili. Now serving as the residence of the Patriarch when visiting, it features beautiful grounds, boxwood gardens, and historic architecture.

Why Martvili Matters

For History Enthusiasts

Martvili represents 1,300+ years of Georgian Christian history compressed into a single site. From its 7th-century origins on a pagan sacred site, through its role educating Georgia’s greatest king, to its survival of Mongol invasions, Ottoman pressure, and Soviet persecution, the monastery embodies Georgia’s turbulent and triumphant history.

The connection to Giorgi Chkondideli and David the Builder makes this monastery directly relevant to understanding Georgia’s golden age—the period when Georgia reached its greatest territorial extent and cultural achievement.

For Art Lovers

The 13th-17th century frescoes, including the Dadiani portraits and works by Byzantine master Cyrus Emanuel Eugenicos, represent outstanding examples of Caucasian medieval art. The evolution of styles across four centuries provides a visual history of Georgian and Byzantine artistic traditions.

For Architecture Students

Martvili demonstrates how Georgian architects adapted the Jvari tetraconch model with creative innovations, creating a distinctly western Georgian style. The comparison between eastern Georgian “solid” churches and western Georgian “lighter” designs is visible here.

For Spiritual Seekers

This is a living monastery where monks and nuns continue traditions established over a millennium ago. The site where pagans once sacrificed children to oak trees now resonates with Christian prayer—a powerful testimony to faith’s transformation of sacred spaces.

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Martvili Monastery founded? The original church was built in the late 7th century. The current main structure dates primarily from the 10th-century reconstruction under King Giorgi II of Abkhazia.

Why is it called “Chkondidi”? “Chkondidi” means “Big Oak” in Megrelian, referring to the ancient sacred oak tree that stood on this site before Christianity. The tree was cut down when the first church was built.

Who was Giorgi Chkondideli? He was the bishop of Chkondidi who became teacher and chief advisor to King David the Builder. The position he held (Chkondidel-Mtsignobartukhutsesi) made him the second most powerful person in Georgia.

Is Martvili Monastery still active? Yes. Since 1998, it has operated as both the St. Andrew the First-Called Father’s Monastery (men) and the St. Nino Nunnery (women). Services are held regularly.

Can I visit the cell where David the Builder was taught? Visitors can see the small cell where tradition says Giorgi Chkondideli taught the young Prince David, though the building has been modified over the centuries.

What’s the difference between Martvili Monastery and Martvili Canyon? They are separate attractions located minutes apart. The monastery is the medieval religious complex on the hilltop; the canyon is the natural gorge carved by the Abasha River.

How far is Martvili from Kutaisi? Approximately 45 km (~1 hour by car). It’s an easy day trip from Kutaisi, often combined with Martvili Canyon.

Is there a cable car to the monastery? Yes, a cable car operates from Martvili town center to near the monastery, offering an alternative to walking or driving up the hill.

What should I wear to visit? Modest dress required: women should cover their heads, shoulders, and knees; men should wear long trousers and cover their shoulders.

Are the frescoes original? The frescoes date from various periods (13th-17th centuries). Some have been conserved with Getty Foundation support, preserving them for future generations.

Conclusion: A Monastery That Shaped History

Standing in Martvili’s courtyard, looking out across the Kolkheti plain toward distant mountains, you occupy the same ground where Giorgi Chkondideli once walked with his young student—the boy who would become David the Builder, unite Georgia, and usher in its golden age.

The massive oak that once stood here is long gone, but a large oak tree still grows in the monastery yard, as if remembering. The infant sacrifices to pagan gods have been replaced by Christian prayers offered continuously for thirteen centuries. The scriptorium where monks translated Greek and Arabic texts into Georgian is silent now, but the manuscripts it produced helped preserve Georgian culture through centuries of invasion.

Martvili survived the Arabs, the Mongols, the Ottomans, and the Soviets. Its frescoes, though faded, still show the faces of Dadiani princes who ruled Samegrelo for centuries. Its stylite tower still stands, though no monk has lived atop it for a hundred years. Its bells still ring for services, as they have since King Giorgi II reconstructed the cathedral over a thousand years ago.

This is not just a monastery. This is a place where history was made—where a teacher shaped a king, where a king transformed a nation, and where Georgia’s golden age took root in the mind of a young prince studying beneath the watchful eye of Giorgi Chkondideli.