Khinkali: The Complete Guide to Georgia’s Famous Dumplings

There is a moment in every Georgian meal when conversation stops. Plates of steaming khinkali arrive at the table, their pleated tops twisted into delicate knots, and everyone reaches in with focused purpose. No forks. No knives. Just hands, hunger, and the promise of that first scalding, broth-filled bite.

I have been eating khinkali across Georgia for over a decade now. From busy Tbilisi restaurants to remote kitchens in Tusheti where grandmothers make them by the hundred. I can tell you this: no other dish captures the Georgian soul quite like khinkali.

What Is Khinkali?

Khinkali (ხინკალი) are Georgian dumplings. But calling them just “dumplings” feels wrong. These hand-crafted parcels of dough hold spiced meat or other fillings, sealed at the top with intricate pleats that form a twisted knob called the kuchi (კუჭი).

What makes khinkali special is not just the filling. It is the broth. When made properly, the meat releases its juices during cooking and creates a pocket of intensely flavored soup trapped inside each dumpling. This broth is the soul of khinkali. Lose it, and you have lost everything.

The dough should be thin enough to be delicate but strong enough to hold without tearing. The pleats, traditionally 19 or more, are not just decorative. They gather the dough evenly so the top cooks at the same rate as the thin walls. A skilled maker can pleat 30 khinkali in the time it takes a beginner to finish one.

The dish comes from the mountainous regions of eastern Georgia: Pshavi, Khevsureti, and Mtiuleti. Shepherds needed portable, hearty food that provided calories and hydration in one package. Perfect for life at high altitude. Today khinkali has spread across the entire country, with each region adding its own twist.

Regional Types of Khinkali

Mtiuluri (მთიულური): The Mountain Original

This is the ancestral khinkali from Mtiuleti region in the Greater Caucasus. Mtiuluri contains coarse-ground beef and pork seasoned with black pepper, cumin, and fresh coriander. Onions go in for both flavor and moisture.

What sets it apart? The meat keeps its texture because it is not ground too fine. And there is a lot of black pepper. Enough to make your lips tingle. This is mountain food. Bold, warming, and unapologetic.

Where to try it: Pasanauri village on the Georgian Military Highway claims to be the birthplace of khinkali. Any restaurant there will serve you authentic Mtiuluri style.

Kalakuri (ქალაქური): City Style

Kalakuri means “city style” and this version reflects Tbilisi taste. The meat is minced much finer, almost like a paste. Fresh herbs like parsley get added. Sometimes garlic too, though purists consider that wrong.

These tend to be milder and slightly smaller. Some say it is an improvement. Others call it a dilution. The debate continues in every Tbilisi khinkali house.

Where to try it: Zakhar Zakharich, Khinklis Sakhli, or any dedicated khinkali restaurant in the capital.

Khevsuruli (ხევსურული): Pure Beef

Khevsureti is a remote highland region known for medieval defensive towers and warrior traditions. Their khinkali uses only beef. No pork at all. The cattle graze on alpine meadows above 2,000 meters and you can taste the difference.

The flavor is cleaner and more mineral. Khevsuruli also uses more dried herbs like blue fenugreek (utskho suneli) since fresh herbs were historically hard to get in these mountains.

Where to try it: In Khevsureti itself around Shatili, or at Tbilisi restaurants that specialize in highland cuisine.

Tushuri (თუშური): The Mutton Version

Tusheti is the most isolated inhabited region in Georgia. You can only reach it three months per year when the mountain pass opens. Sheep dominate the local economy, so Tushuri khinkali uses mutton, sometimes mixed with beef.

The taste is richer and gamier. Fat content runs higher which means more broth. If you appreciate mutton, these are exceptional. The spicing stays simple to let the meat flavor come through.

Where to try it: Omalo village during summer season (July to September), or Tushuri restaurants in Telavi and Tbilisi.

Pankisi Khinkali: The Best I Have Ever Had

I need to be honest here. The finest khinkali I have ever eaten were not in a famous restaurant. They were in Pankisi Gorge, made by Kist women in a family kitchen.

The Kists are ethnic Chechens who settled in Pankisi Valley centuries ago. They make khinkali with pure mutton, spiced according to their own traditions that blend Georgian and North Caucasian influences. The sheep had been grazing on the hillside that same morning. The broth was rich without being heavy. The pleating was perfect.

What made them unforgettable was not just the technique. It was eating them cross-legged on a carpet, the Alazani River visible through the window, hosts refilling my plate faster than I could empty it. This is what food means in the Caucasus. Hospitality made edible.

Pankisi is not on standard tourist routes. That is exactly why it stays special. If you want to experience this, we can arrange visits with local families who welcome guests.

Khinkali with Apkhoti (აფხოტი): Dried Meat from Javakheti

In the volcanic highlands of Samtskhe-Javakheti, where Georgian and Armenian cultures mix, you find khinkali made with apkhoti. This is traditional dried meat, a preservation method essential in a region with brutal winters and no refrigeration historically.

Apkhoti produces intensely concentrated beef with a slight chew and deep umami. The khinkali are richer and saltier than fresh meat versions. The dried meat rehydrates a bit during cooking but keeps its distinctive texture.

These are not common even in Javakheti today. You need to ask specifically at local guesthouses around Akhalkalaki.

Tsero Khinkali (წერო ხინკალი): A Different Dish Entirely

Tsero khinkali is actually not a dumpling at all. It is a separate dish that shares only the name. Small pieces of plain dough are boiled and then dressed with fried onions, matsoni (Georgian yogurt), garlic sauce, and crushed walnuts.

Think of it as Georgian comfort pasta rather than a dumpling. The combination of tangy matsoni, sweet caramelized onions, pungent garlic, and rich walnuts creates something simple but satisfying. It is peasant food in the best sense.

You will find tsero khinkali in home kitchens more often than in restaurants. It is the kind of thing Georgian grandmothers make when they want something quick and filling.

Vegetarian and Vegan Khinkali

Georgian food centers on meat for celebrations. But khinkali offers real meatless options that are not afterthoughts.

Cheese Khinkali (ყველით)

Fresh Georgian cheese, usually imeruli or sulguni, mixed with herbs. No broth here. The pleasure is textural: thin dough giving way to molten, stretchy cheese. Eat them almost too hot when the cheese pulls in strings.

Quality varies a lot depending on how fresh the cheese is. Most khinkali restaurants in Georgia serve these.

Dambal Khacho (დამბალ ხაჭო): The Rare Fermented Cheese Version

This needs explanation. Dambal khacho is a traditional fermented cheese from mountain regions. Pungent, complex, nothing like the mild fresh cheeses most visitors encounter. Think of it as Georgia’s answer to blue cheese.

Regular restaurants do not offer dambal khacho khinkali. But in the village of Bulachauri, I once asked a family to make them for me. They agreed. The result was extraordinary. Sharp, funky, unlike anything else.

But here is the important part: you must eat them immediately while hot. As they cool, the cheese’s texture becomes unpleasant, and the intense flavors overwhelm rather than harmonize. This is not a menu item. It requires advanced arrangements with village families who have access to real dambal khacho.

Mushroom Khinkali (სოკოთი)

Wild mushroom khinkali appear more often now, especially in autumn when Georgian forests produce abundant fungi. The best versions use mixed wild mushrooms like chanterelles, porcini, and honey mushrooms, sauteed with onions before wrapping.

Mushrooms release liquid but do not create broth the way meat does. Good mushroom khinkali are deeply savory. Georgian mushroom varieties have remarkable depth. They are delicious on their own terms rather than as a meat substitute.

Where to try them: Autumn season at quality khinkali houses, or by request using dried mushrooms year round.

Potato Khinkali (კარტოფილით)

The simplest vegan option. Mashed potatoes seasoned with onions and herbs. These are comfort food. Filling, mild, satisfying. They appear often during Lenten season when observant Orthodox Georgians avoid animal products.

Honestly? They are fine. Pleasant but unremarkable compared to meat or mushroom versions. Try them once for completeness, then focus your appetite elsewhere.

How to Eat Khinkali Properly

Eating khinkali wrong is easy. Eating them right takes instruction. Georgians take this seriously. Watch any local’s face when a tourist cuts into khinkali with a knife and spills precious broth across the plate.

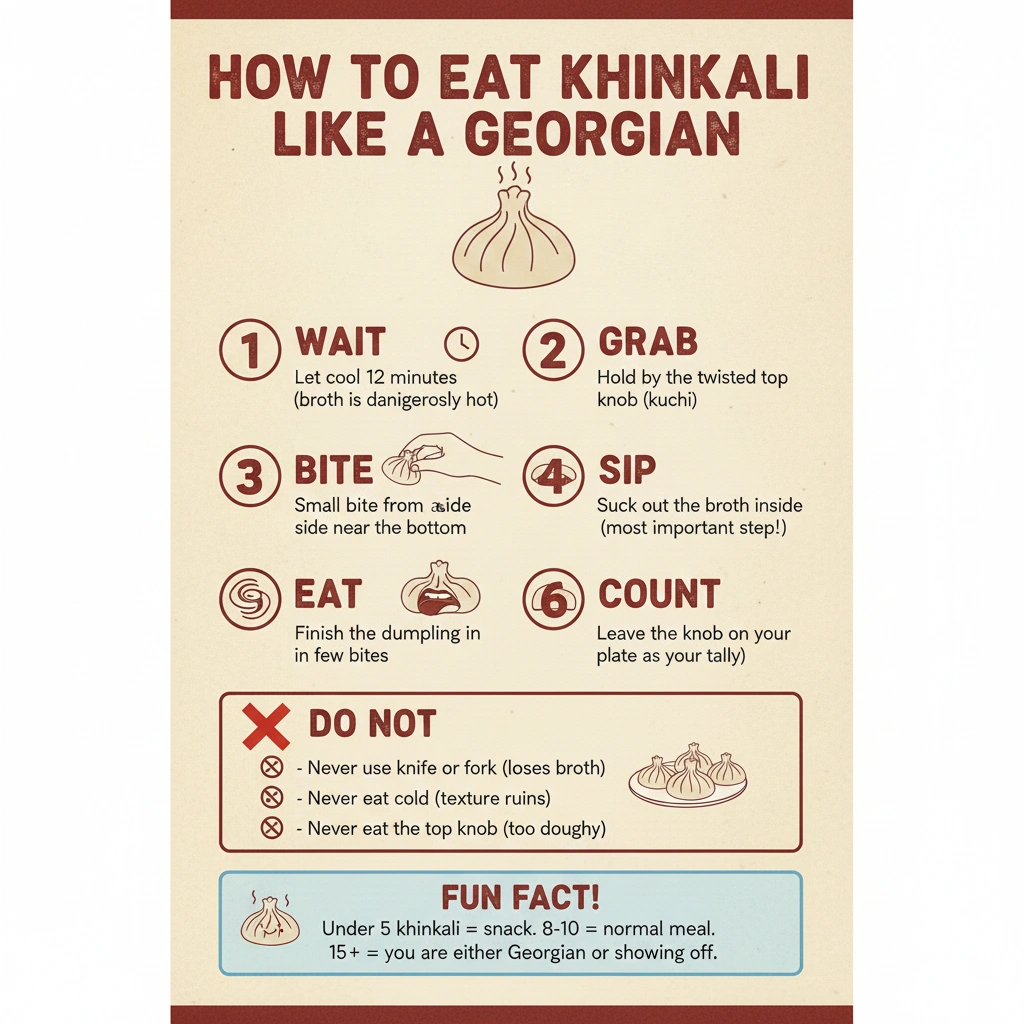

Here is the correct method:

- Wait briefly for cooling. Fresh from the pot, khinkali are dangerously hot. The broth inside can cause real burns. One or two minutes of patience prevents injury.

- Pick up by the knob (kuchi). The twisted pleated top exists as a handle. Grab it with your fingers. This is hand food. No utensils.

- Bite the side near the bottom. Take a small bite to pierce the dough wall and create an opening.

- Suck out the broth. This is crucial. Tilt the khinkali and draw out the soup inside. This broth is concentrated meat essence. Wasting it is a tragedy.

- Eat the rest. Once the broth is safely consumed, finish the dumpling in a few bites.

- Leave the knob on your plate. The dough top is thick and chewy. Traditionally, you do not eat it. The pile of kuchis on your plate counts how many you have consumed. Under five is a light snack. Eight to ten is respectable. Above that, you are either a local or showing off.

- Season if you want. Black pepper is traditional. Some add a splash of vinegar or adjika (spicy pepper paste). Purists eat them plain.

What not to do:

- Never cut khinkali with a knife or fork. You will lose the broth instantly.

- Do not let them sit too long. Lukewarm khinkali lose their magic. Cold ones are genuinely unpleasant.

- Do not fill up on bread first. Khinkali are substantial. Arrive hungry.

Khinkali vs Other Dumplings: What Makes Them Different

Every culture with cold winters developed some form of meat in dough. But Georgian khinkali stand apart from their relatives around the world.

Khinkali vs Russian Pelmeni

Pelmeni are small, often frozen in bulk, and boiled as everyday food. The dough to meat ratio favors dough. The filling is dense and compact. You eat dozens at a sitting, usually covered in sour cream or butter.

Khinkali are larger, always made fresh (freezing destroys the broth pocket), and put the meat experience front and center. You might eat five to eight. The broth inside has no pelmeni equivalent. Pelmeni are solid throughout.

Cultural context matters too. Pelmeni are a workhorse food. Khinkali are celebratory. You do not invite guests over for pelmeni. You absolutely invite them for khinkali.

Khinkali vs Central Asian Manti

Manti from Turkey, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and surrounding regions are steamed or baked rather than boiled. This produces chewy dough instead of soft. They come with yogurt sauce and spiced butter, becoming part of a dressed dish rather than standing alone.

Size varies by region, but most manti are smaller than khinkali. The flavor profile goes toward lamb and onion with different spices. Often paprika, sometimes sumac. Middle Eastern and Central Asian influences rather than Caucasian.

The eating method differs completely. Manti is a fork food eaten from a sauced plate. The ritualized hand eating of khinkali has no manti parallel.

Khinkali vs Himalayan Momo

Momos share the hand-eating tradition and similar size, making them perhaps the closest global relative. Both can have broth-filled interiors when done well. Both feature pleated seals.

Differences show in the details. Momo dough often includes oil for a slightly richer texture. Fillings tend toward more aromatics: ginger, garlic, sometimes curry spices reflecting South Asian influence. Momos are usually steamed rather than boiled. They almost always come with dipping sauces, typically tomato or sesame based.

The family resemblance is strongest here. Both likely share ancestry along ancient trade routes. If you love momos you will probably love khinkali, and the reverse holds true.

What Makes Khinkali Unique

Three things distinguish khinkali from all relatives:

The broth. The quantity and intensity of soup inside well made khinkali exceeds comparable dumplings anywhere. It is not just juice from cooked meat. It is a concentrated essence.

The ritual. The specific eating method, the pile of accumulated kuchis, the communal atmosphere. Khinkali eating is a performance as much as nourishment.

The freshness requirement. You cannot adequately freeze khinkali. This limits commercial export and ensures the best ones exist only in Georgia, made hours or minutes before you eat them. Authenticity is geographically bounded in a way few foods still are.

Where to Eat Khinkali: Our Recommendations

In Tbilisi

- Zakhar Zakharich – Consistent quality, good variety, open late

- Pasanauri (the restaurant) – Tourist-friendly but genuinely good

- Khinklis Sakhli No. 1 – Local favorite, no frills atmosphere

On the Georgian Military Highway

- Pasanauri village – Multiple family restaurants. Ask for Mtiuluri style. The best is the restaurant Guda.

- Roadside stops near Gudauri – Quality varies but freshness is guaranteed

In Kakheti

- Signagi and Telavi – Many options. Request Tushuri if available

For Adventurous Eaters

- Pankisi Gorge – By arrangement with local families

- Javakheti – For apkhoti versions, ask at guesthouses around Vardzia.

Experience Khinkali on Your Georgia Trip

We include khinkali in many of our tours. Not just restaurant meals but cooking classes where you learn the pleating technique, visits to mountain villages where regional styles originated, and meals in family homes where khinkali are made fresh for guests.

Want to build a trip around Georgian food traditions? Our Kakheti wine tours combine winery visits with traditional meals. Our Kazbegi day trips stop in Pasanauri, the town claiming to be the birthplace of khinkali. And our multi-day Tusheti adventures include authentic Tushuri khinkali in settings no restaurant can match.

Have questions about Georgian food or want to plan a culinary focused trip? Contact us. We are always happy to talk khinkali.