Khatskhi pillar

On a 40-meter limestone pillar rising from a Georgian valley, a monk lived for twenty years—continuing a tradition begun in Syria in 423 AD when St. Simeon climbed his first column to escape worldly temptations. In 1944, mountaineers ascending Katskhi Pillar found the skeleton of his medieval predecessor, still waiting after 600 years. This is the story of Georgia’s most extraordinary monastery.

The Church in the Sky

Rising like a finger pointing toward heaven from the valley floor near Chiatura, the Katskhi Pillar (კაცხის სვეტი) is one of the world’s most isolated and extraordinary religious sites—a 40-meter (130-foot) natural limestone monolith with a medieval church perched improbably on its summit.

For centuries, locals gazed up at the visible ruins, knowing a church existed on top but having no idea how to reach it. They called it the “Pillar of Life” and revered it as a symbol of the True Cross. Legends surrounded it. One story claimed an iron chain once connected the pillar’s summit to the dome of a village church 1.5 kilometers away.

The truth proved stranger than legend. When mountaineers finally climbed the pillar in 1944, they discovered the ruins of a 9th-10th century hermitage, the bones of the last monk who died there some 600 years earlier, and evidence of a remarkable tradition: stylite monasticism—the practice of living atop pillars to achieve spiritual closeness to God.

In the 1990s, a Georgian monk named Maxime Qavtaradze revived this ancient tradition, living on the pillar for over 20 years and restoring the ruined church. Today, Katskhi Pillar stands as both a monument to medieval Georgian Christianity and a living testimony to ascetic devotion that continues into the 21st century.

Quick Overview:

- Height: ~40 meters (130 feet)

- Top surface: ~150 m² (1,600 sq ft)

- Medieval structures: 9th-10th century

- Revived: 1993-1995 by Monk Maxime Qavtaradze

- Restored: 2005-2009 with state support

- Location: Village of Katskhi, near Chiatura, Imereti

- Distance: ~200 km from Tbilisi, ~70 km from Kutaisi

- Public access to summit: Prohibited since 2018 (monks only)

The Stylites: Pillar-Saints of the Christian World

St. Simeon Stylites and the Birth of a Tradition

To understand Katskhi Pillar, you must first understand the stylites (from Greek stylos, meaning “pillar”)—Christian ascetics who chose to live atop columns as a form of extreme devotion.

The first and most famous stylite was St. Simeon Stylites the Elder (c. 390–459), a Syrian monk who climbed a pillar near Aleppo in 423 AD and remained there for 36 years until his death. He began on a column just 3 meters high but eventually moved to one 15 meters tall.

Why live on a pillar? Simeon wanted to escape the crowds of pilgrims who sought his counsel, leaving him no time for prayer. Ironically, his pillar made him more famous—thousands came to see the holy man who stood between earth and heaven. He preached from his platform, offered counsel, and became one of the most influential religious figures of his era.

Simeon’s example inspired imitators across the Byzantine world:

- Daniel the Stylite (409–493) lived 33 years on his pillar near Constantinople

- Simeon Stylites the Younger (517–592) spent 68 years on various pillars near Antioch

- St. Alypius lived on a pillar near Adrianopolis in the 7th century

- The practice continued in Russia until 1461 and among Ruthenians even later

Stylites in Georgia

Georgia, with its strong ties to Byzantine Christianity, adopted the stylite tradition. The Katskhi Pillar became one of the most dramatic expressions of this practice—a natural rock formation that offered an even more extreme challenge than man-made columns.

Georgian stylites lived on Katskhi from at least the 9th century through the 15th century, when the Ottoman invasion of Georgia disrupted monastic life throughout the country. For 500 years afterward, the pillar stood abandoned, its ruins visible but unreachable, surrounded by legend and mystery.

The Pillar’s History: From Pagan Shrine to Christian Hermitage

Before Christianity: The Fertility God

According to Prince Vakhushti Bagrationi, the 18th-century Georgian historian and geographer who provided the first written description of the pillar, Katskhi may have served as a pagan shrine before Georgia’s conversion to Christianity in the 4th century.

Local tradition held that the pillar was associated with a fertility god—a common theme in pre-Christian Caucasian religions. The dramatic natural formation would have been an obvious focus for spiritual veneration.

Christianization: 6th Century

The pillar’s transformation into a Christian site likely occurred in the 6th century. Evidence for this includes a carved cross at the base of the pillar that archaeologists have dated to this period, similar to early medieval crosses found elsewhere in Georgia, particularly at Bolnisi.

This pattern—converting pagan sacred sites to Christian ones—was common throughout the Christianizing world. The pillar’s awesome natural presence made it an ideal candidate for appropriation.

The Medieval Hermitage: 9th-10th Century

The structures visible on the pillar’s summit today date primarily to the 9th-10th century, based on systematic archaeological studies conducted from 1999 to 2009. This was a period of intense monastic activity in Georgia, following the great monastic colonization of Tao-Klarjeti led by St. Gregory of Khandzta.

What the medieval complex included:

- Church of St. Maximus the Confessor: A small hall church measuring just 4.5 x 3.5 meters (15 x 11 feet)

- Three hermit cells: For the monks who lived on the summit

- Crypt/burial vault: 2 x 1 meters, where deceased stylites were interred

- Wine cellar: With eight qvevri (traditional Georgian clay wine vessels)—suggesting the monks made wine even atop their pillar

- Curtain wall: Defensive wall around the irregular summit

The presence of a wine cellar is particularly interesting. It suggests that while the Katskhi stylites practiced severe asceticism, they weren’t quite as extreme as St. Simeon, who reportedly subsisted only on bread and goat milk.

The 13th-Century Inscription

In 2007, archaeologists discovered a small limestone plate with an inscription in Asomtavruli (the oldest Georgian script), dated paleographically to the 13th century.

The inscription reveals that a man named “Giorgi” was responsible for building three hermit cells on the pillar—apparently as an act of atonement for his sins. It also mentions the “Pillar of Life”, confirming that this name was already in use 800 years ago.

This inscription proves the hermitage was still active in the 13th century, three centuries after its founding.

Abandonment: 15th Century

Historians believe the Katskhi hermitage was abandoned sometime in the 15th century, likely due to the Ottoman invasion of Georgia and the general disruption of monastic life during this period.

The last stylite to live on the pillar died there. His bones remained in the crypt for roughly 600 years, until their discovery in 1944.

The 1944 Discovery: First Modern Ascent

Prince Vakhushti’s Mystery

For centuries, the ruins on Katskhi Pillar tantalized observers who could see them but not reach them. Prince Vakhushti Bagrationi wrote in his 18th-century Geographic Description of the Kingdom of Georgia:

“There is a rock within the ravine standing like a pillar, considerably high. There is a small church on the top of the rock, but nobody is able to ascend it; nor know they how to do that.”

This mystery persisted until the 20th century.

Alexander Japaridze’s Expedition

In July 1944, a group led by Georgian mountaineer Alexander Japaridze and writer Levan Gotua made the first documented modern ascent of the Katskhi Pillar.

What they found was extraordinary:

- Ruins of two churches (initially dated to the 5th-6th centuries, later revised to 9th-10th century)

- Cramped living quarters for monks

- Qvevri (traditional Georgian wine vessels) in a ruined wine cellar

- The skeleton of a stylite—the last monk to live and die on the pillar, some 600 years earlier

The bones—now known as the “Katskhi Pillar skeleton”—were found in the crypt beneath the church, where the monk had presumably been buried by colleagues who descended the pillar for the final time after his death.

Subsequent Research

Architecture specialist Vakhtang Tsintsadze, who was part of the 1944 expedition, published the first academic paper on the findings in 1946. His initial dating of the structures to the 5th-6th centuries was later revised.

From 1999 to 2009, more systematic archaeological research was conducted. Giorgi Gagoshidze of the Georgian National Museum re-dated the structures to the 9th-10th century based on architectural analysis and artifacts. The discovery of the wine cellar and qvevri also modified understanding of how extreme the Katskhi asceticism actually was.

Maxime Qavtaradze: The Modern Stylite

From Prison to Pillar

The most remarkable chapter in Katskhi’s story began in 1993 when a Georgian Orthodox monk named Maxime Qavtaradze decided to revive the stylite tradition.

Qavtaradze’s path to the pillar was unconventional. A native of Chiatura, he spent his youth in trouble—by his own account, he “drank, sold drugs, everything.” He served time in prison. During the Soviet era, he worked as a crane operator, which gave him a head for heights that would later serve him well.

After his release from prison, Qavtaradze took monastic vows in 1993 and found his calling in the abandoned pillar that had fascinated locals for centuries. He felt that living atop Katskhi would help him “move closer towards God and let go of his past.”

As Qavtaradze himself explained:

“It is up here in the silence that you can feel God’s presence.”

The First Years

When Qavtaradze arrived at the pillar in the mid-1990s, there was nothing on top but ruins. For his first two years, he slept inside an old refrigerator to protect himself from the elements—perhaps the strangest monk’s cell in Christian history.

With permission from Patriarch Ilia II, the spiritual leader of the Georgian Orthodox Church, and assistance from mountaineers, local villagers, and eventually the Georgian government, Qavtaradze began restoring the medieval church and hermitage.

Life on the Pillar

For over 20 years, Qavtaradze lived primarily on top of the Katskhi Pillar, coming down only once or twice a week. His daily life included:

- Seven hours of prayer daily, including night prayers from 2 AM until sunrise

- Ascending and descending via a 40-meter iron ladder (a 20-minute climb each way)

- Receiving provisions via a winch operated by supporters on the ground

- Counseling troubled young men who came to the monastery below seeking guidance

Despite his isolation, Qavtaradze was not entirely cut off from the world. He ministered to the men who gathered at the monastery at the pillar’s base—many of them, like his younger self, struggling with addiction, divorce, or other crises.

The Documentary: “The Stylite”

In 2013, a documentary film called “The Stylite” brought international attention to Qavtaradze and his extraordinary life. Photographer Amos Chapple also ascended the pillar to document the monk’s existence, producing images that circulated worldwide.

Qavtaradze expressed his intention to be buried in the same crypt as his medieval predecessor:

“Of course!” he replied when asked if his bones would join those of the stylite who died 600 years ago.

Current Status

According to some reports, Father Maxime no longer lives full-time on the pillar but continues to make regular ascents. The Church of St. Maximus the Confessor on the summit has been fully restored, and the monastery complex at the base—including the new Church of Simeon Stylites—is active.

In 2018, Patriarch Ilia II issued an edict prohibiting public access to the top of the pillar. Only monks are now permitted to make the climb.

What Exists at Katskhi Today

On Top of the Pillar

The summit of Katskhi Pillar (~150 m² / 1,600 sq ft) contains:

Church of St. Maximus the Confessor

- Small hall church (4.5 x 3.5 meters)

- Restored version of the medieval church

- Dedicated to the 7th-century Byzantine monk and theologian

Crypt/Burial Vault

- 2 x 1 meters

- Contains the bones of the medieval stylite discovered in 1944

- Father Maxime intends to be buried here as well

Three Hermit Cells

- Restored from the medieval ruins

- One served as Qavtaradze’s living quarters

Wine Cellar

- Where eight qvevri were discovered during excavations

Curtain Wall

- Defensive wall encircling the uneven summit

At the Base

Church of Simeon Stylites

- Newly built church named after the first stylite

- Features frescoes and a small altar

- Open to visitors for prayer and candle-lighting

Monastery Complex

- Living quarters for monks

- Dormitories for troubled men seeking spiritual guidance

- The community prays seven hours daily

6th-Century Cross

- Carved into the rock at the pillar’s base

- One of the oldest Christian symbols at the site

- Visitors can climb to the first level of the pillar to see it

Historic Ruins

- Remains of an old wall and belfry

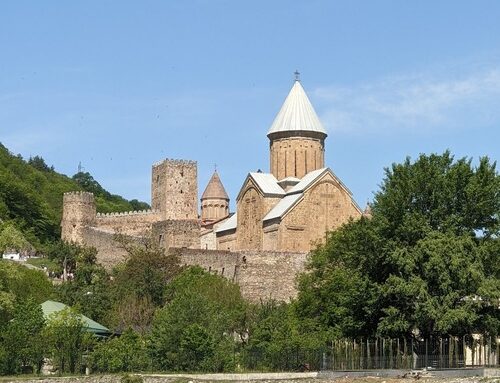

The Nearby Katskhi Monastery (Village Church)

Don’t confuse the Katskhi Pillar with the Katskhi Monastery (also called the Katskhi Church) located in the same village, about 1.5 kilometers away.

This is the village church that legend once claimed was connected to the pillar by an iron chain.

Key facts about Katskhi Monastery:

- Built 1010-1014 under King Bagrat III of Georgia

- Founded by the nobleman Rati of the Liparitid (Baguashi) family

- Unique octagonal/hexagonal design—unusual in Georgian architecture

- Dedicated to the Holy Trinity (also called Nativity of the Savior)

- Served as the burial ground for the Liparitid dynasty

- Features rich ornamental carving

- Closed by Soviets in 1924, revived in 1990

The Katskhi Monastery is worth a separate visit for its remarkable architecture and as a complement to the pillar site.

Visiting Katskhi Pillar: Complete Practical Guide

Location and Getting There

Katskhi Pillar is located in the village of Katskhi in the Imereti region of western Georgia, approximately 5-11 km from the town of Chiatura.

Distances:

- From Tbilisi: ~200-220 km (3-3.5 hours by car)

- From Kutaisi: ~60-70 km (1-1.5 hours by car)

- From Chiatura: ~5-11 km (15-20 minutes by car)

By Car: From the main road, look for signposts directing you to two parking areas:

- First parking lot: More distant, offers good photographic views

- Second parking lot: Closer to the pillar

The final approach involves a 20-minute walk/hike from the parking area to the pillar itself. The path can be rough—wear sturdy shoes.

By Public Transport:

- Take a marshrutka from Tbilisi’s Didube station to Chiatura (3-3.5 hours)

- From Chiatura, take a taxi or local marshrutka to Katskhi village

Marshrutkas between Kutaisi and Chiatura also run regularly.

By Organized Tour: Many tour companies offer day trips from Tbilisi or Kutaisi combining Katskhi Pillar with Chiatura’s cable cars and/or other Imereti attractions.

What You Can (and Cannot) Do

You CAN:

- Visit the Church of Simeon Stylites at the base

- Pray and light candles inside the church

- Walk around the monastery grounds

- Climb to the first level of the pillar to see the 6th-century cross

- Photograph the pillar and surroundings (from below)

- Speak with the monks (they’re welcoming to respectful visitors)

- Purchase monastery products if available

You CANNOT (since 2018):

- Climb to the top of the pillar—only monks are permitted

- Access the monastery buildings (visible but off-limits)

Exception: Men who wish to stay at the monastery for spiritual guidance must:

- Receive permission

- Live in a cell with the monks for at least a week

- Participate in all religious rituals (seven hours of prayer daily)

- Pass rigorous examination

Dress Code

As an active Orthodox monastery:

- Women: Cover head (scarves available), shoulders covered, long skirt or dress

- Men: Long trousers, shoulders covered

- Remove hats (men) inside churches

- Behave quietly and respectfully

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (April-June) and Autumn (September-October): Pleasant weather, beautiful scenery

- Early morning or late afternoon: Best light for photography

- Avoid midday in summer: Can be very hot

Time Needed

- 30-45 minutes: Quick visit, photos from below, church visit

- 1-1.5 hours: More thorough exploration, speaking with monks

- Half day: Combined with Chiatura cable cars or Katskhi Monastery

Combining Katskhi with Chiatura

A visit to Katskhi Pillar combines perfectly with Chiatura, Georgia’s extraordinary Soviet-era mining town just a few kilometers away.

Chiatura: The Cable Car City

Why Chiatura is remarkable:

- Founded in late 1800s around manganese deposits

- By 1905, produced 60% of world’s manganese output

- In 1954, Stalin (who had connections to Chiatura from his revolutionary days) authorized an extensive cable car system to transport miners

- Original 17 cable car lines totaling over 6 km

- Workers called the system “rope road”

- Original rusted Soviet cars operated until 2021

- System renovated 2017-2021 by French company Poma

- Modern cars now operate safely with stunning views

What to see in Chiatura:

- New cable car system: Four lines from Central Station (50 tetri one-way, operates 8am-8pm with 2-3pm break)

- Old cable car stations: Some still visible with Soviet-era murals and architecture

- Chiatura Museum of Local Lore: Documents mining history with archival photos and equipment (5 GEL, 10am-6pm)

- Soviet architecture and atmosphere: Apartment blocks, industrial ruins, time-capsule feeling

- Mgvimevi Monastery: Cave monastery near Chiatura, worth visiting

Suggested Itineraries

Half-Day from Kutaisi: Kutaisi → Katskhi Pillar (1 hour) → Chiatura cable cars and town (1.5 hours) → return to Kutaisi

Full Day from Tbilisi: Tbilisi → Chiatura (3 hours) → Cable cars and museum → Katskhi Pillar → Return to Tbilisi Or continue to Kutaisi and explore western Georgia

Imereti Exploration (Full Day from Kutaisi): Kutaisi → Katskhi Pillar → Chiatura → Ubisa Monastery → return to Kutaisi

Why Katskhi Pillar Matters

For Spiritual Seekers

Katskhi represents one of Christianity’s most extreme expressions of the desire to draw closer to God by withdrawing from the world. The stylites believed that by rising physically above the earth, they could achieve spiritual heights unreachable at ground level.

Father Maxime’s revival of this tradition in the 1990s—transforming himself from a drug dealer and prisoner into a pillar-dwelling monk—is a powerful testament to the possibility of radical spiritual transformation.

For History Enthusiasts

The pillar preserves evidence of Georgian monasticism spanning more than a millennium:

- 6th-century cross marking the site’s Christianization

- 9th-10th century hermitage from Georgia’s medieval flowering

- 13th-century inscription documenting continued use

- 15th-century skeleton of the last medieval stylite

- 20th-21st century revival by Father Maxime

For Architecture and Archaeology Lovers

The Katskhi complex offers insights into:

- How medieval Georgians adapted natural formations for religious purposes

- The building techniques used to construct on such impossible terrain

- The lifestyle of pillar-dwelling monks (those qvevri raise fascinating questions!)

- The process of modern restoration of medieval structures

For Adventurous Travelers

Few places in the world combine:

- A dramatic natural formation

- A virtually inaccessible church

- Living religious tradition

- A modern hermit’s story of redemption

- Proximity to a Soviet-era cable car city

Katskhi Pillar is simply unlike anywhere else on earth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I climb to the top of Katskhi Pillar? No. Since 2018, only monks are permitted to ascend. Visitors can climb to the first level to see the 6th-century cross.

Who was the last person to live on the pillar? Monk Maxime Qavtaradze lived primarily on the pillar from 1993 until around 2015, spending over 20 years there. He still makes regular ascents.

What happened to the skeleton found in 1944? The bones of the medieval stylite remain in the crypt beneath the church on the pillar’s summit.

How do monks reach the top? Via a 40-meter iron ladder installed during the restoration. The climb takes about 20 minutes.

Is the monastery at the base open to visitors? The Church of Simeon Stylites is open for prayer and candle-lighting. The monastery living quarters are not accessible to casual visitors.

Can women visit Katskhi Pillar? Women can visit the base and the Church of Simeon Stylites. However, following the tradition established by St. Simeon himself, women are not permitted to climb the pillar or stay at the monastery for spiritual retreats.

How far is Katskhi from Kutaisi/Tbilisi? ~60-70 km from Kutaisi (1-1.5 hours), ~200-220 km from Tbilisi (3-3.5 hours)

What’s the difference between Katskhi Pillar and Katskhi Monastery? The Pillar is the 40-meter rock with the church on top. The Monastery (also called Katskhi Church) is a separate 11th-century octagonal church in the same village, about 1.5 km away.

Should I combine Katskhi with Chiatura? Absolutely. The Soviet-era cable car city is just a few kilometers away and makes a perfect complement to the pillar visit.

Conclusion: Between Earth and Heaven

Standing at the base of Katskhi Pillar, gazing up at the tiny church perched impossibly on its summit, you witness something that shouldn’t exist—and yet has existed for over a thousand years.

The stylites believed that by climbing above the earth, they could leave behind their earthly selves and approach the divine. Father Maxime, ascending his 40-meter ladder twice weekly, continues that tradition—a former prisoner who found redemption on a pillar in the Georgian countryside.

Whether you come as a pilgrim, a history buff, or simply a traveler seeking the extraordinary, Katskhi Pillar delivers something you won’t find anywhere else: a place where the boundary between earth and heaven becomes, quite literally, a matter of 40 meters and an iron ladder.